Great things are happening in education, but too frequently success occurs in pockets. There is a path to scaling effective innovations, but beware of falling for misconceptions that lead us down side roads of disappointment and blame. Scaling innovation is a process that recognizes teachers as thoughtful learners and learners as insightful teachers.

Misconception 1: Making current practices more efficient is innovation.

There are plenty of technology tools that improve the efficiency of traditional and mundane classroom practices (e.g., taking attendance, entering grades). While these tools are helpful, they should not be confused with innovation. True innovation in education enables teachers and learners to do something new, not just faster. Real innovation in education designs with the future in mind.

Misconception 2: Technical training equals professional learning.

In order for new edtech tools to be adopted in innovative ways, professional learning opportunities need to go beyond point and click and tech support. Lately, it’s been trendy to say, “Why should teachers need PD to use well-designed technology? Nobody needs PD to use an iPhone.” The iPhone assumption is a huge fallacy when it comes to innovative classroom practices.

Redesigning learning experiences based on the new opportunities made possible with an innovative tool requires deep thinking, conversation with other educators, and time for experimentation. Without this type of deep professional learning, new tools are used in old ways. Document cameras become overhead projectors. Interactive whiteboards are chalkboards. Professional learning for education innovation should consider how a new tool or technique will transform how students access information, express understanding, and engage in learning (Universal Design for Learning principles) – not just how they log in.

Misconception 3: Seeing is believing.

This myth is probably the most important to dispel, because – in fact – seeing is often disbelieving. I’ve witnessed this scenario on multiple occasions: A group of educators are watching a highly produced video featuring a teacher and classroom of students implementing an innovative practice. The initial reaction: “That doesn’t look like our school or our classrooms.” And disbelief immediately sets in.

In a video clip of a classroom, what’s most visible? Student demographics, furniture layout, equipment condition. What’s not visible? The instructional planning process, the built-in routines for supporting students, all the times before when everything didn’t work perfectly. When watching another classroom, the most visible aspects are often the superficial things that actually become distractions. The most important lessons to be learned are typically invisible to the naked eye.

Simply seeing, hearing, or reading about an innovative approach will not lead to spreading adoption. Scaling innovation requires an education MVP and a process for validating learning.

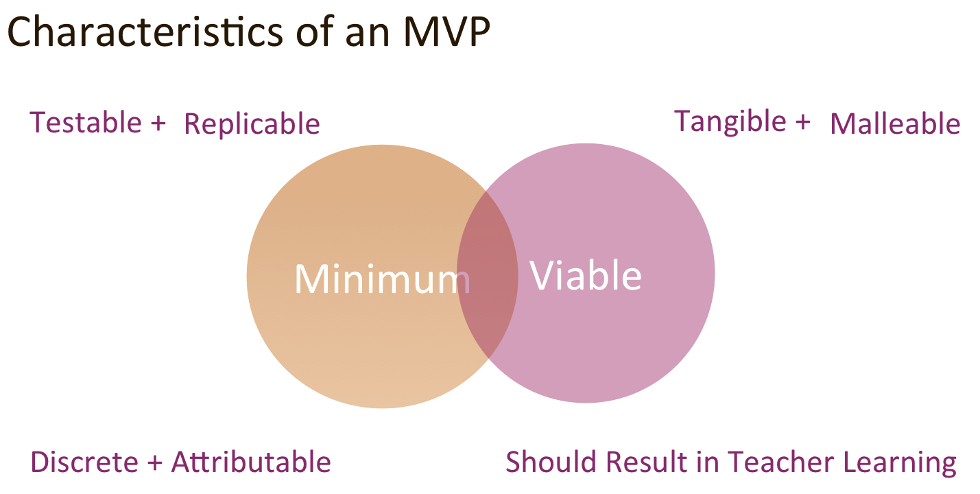

I borrow this phrase, MVP, from Eric Ries’ The Lean Startup, and I’ve written a previous blog series about applying lean to education. When applied to education, I define MVP as the minimum viable practice – a clear agreement as to what elements of an instructional idea need to be in place to collect the maximum amount of learning about teacher implementation and student progress.

The education MVP is:

- Testable and Replicable. There are clear steps for implementation so that the instructional practice can be applied effectively in multiple classrooms.

- Tangible and Malleable. The practice is concretely defined and captured in a way that can be revised and updated.

- Discrete and Attributable. Educators define metrics to measure progress on specific student learning objectives.

When we work with schools to scale innovation, we use a lessoncast as the education MVP to facilitate the teach – measure – learn cycle. Educators capture and define the innovative practice via the lessoncast format. Teachers implement the idea and measure student learning. Then as a community of educators, we reflect on our results to inform our teacher learning about what really works to improve student learning.

Scale does not equal blind replication across settings. This cycle takes time, willingness to iterate, and openness to learning. And quite often the key to validated learning is to listen to our students. This requires providing opportunities for students to articulate when something is or isn’t working and helping them become conscious advocates for themselves as learners. When scaling innovation in education, everyone’s a teacher and everyone’s a learner.